(Photo by Bill Roth / Alaska Dispatch News)

John’s death has a deep and far-reaching impact on the state, as he was viewed as a cultural leader and advocate. He is remembered for teaching traditional ways of life and knowledge, teaching through symbolic traditional stories, and encouraging Yup’ik people to continue speaking in their native language. He contributed to numerous books and publications with his cultural perspectives, ensuring the Yup’ik traditions remain preserved.

John’s teachings, among those of many other respected community elders and leaders, are being taken to heart in one small corner of a world increasingly impacted by globalization, and the continued spread of ideas, language, and customs. Despite the growing merging of cultures, and gradual disappearance of traditional cultures and languages, Yup’ik Alaska Native communities continue to seek cultural preservation.

Language and Cultural Identity

Language is just one of the many elements of culture, but its influence is significant. The link between language and culture is strong, as language gives people the ability to communicate ideas and concepts unique to that culture, and affects a person’s perception of the world around them. The health of a culture’s language is often an indicator of the strength of the culture as a whole.

The Enduring Voices project describes the crucial role language plays in preserving culture:

“Language defines a culture, through the people who speak it and what it allows speakers to say. Words that describe a particular cultural practice or idea may not translate precisely into another language. Many endangered languages have rich oral cultures with stories, songs, and histories passed on to younger generations, but no written forms. With the extinction of a language, an entire culture is lost.”

A look at the current state of languages in the world indicates that cultures are struggling to survive in modern society, where communication, transportation, and technology have heavy impacts on a global scale.

Of the 7,000 languages in the world today, approximately 35% are classified as in trouble or dying. It is projected that 90% of the world’s languages will be lost by the end of the century.

Indigenous cultures such as Yup’ik represent a large portion of languages and cultures that are threatened. Approximatley 6,000 languages are spoken by indigenous people, meaning 71% of the world’s languages are spoken by only 5% of the world’s population.

Yup’ik: A Struggling, yet Surviving, Culture and Language

A visit to a Yup’ik village in the bush of Alaska, such as John’s home town of Toksook Bay, reveals a strong sense of culture. From subsistence hunting to traditional dance, from language use to cultural values and traditions, Yup’ik culture is evident.

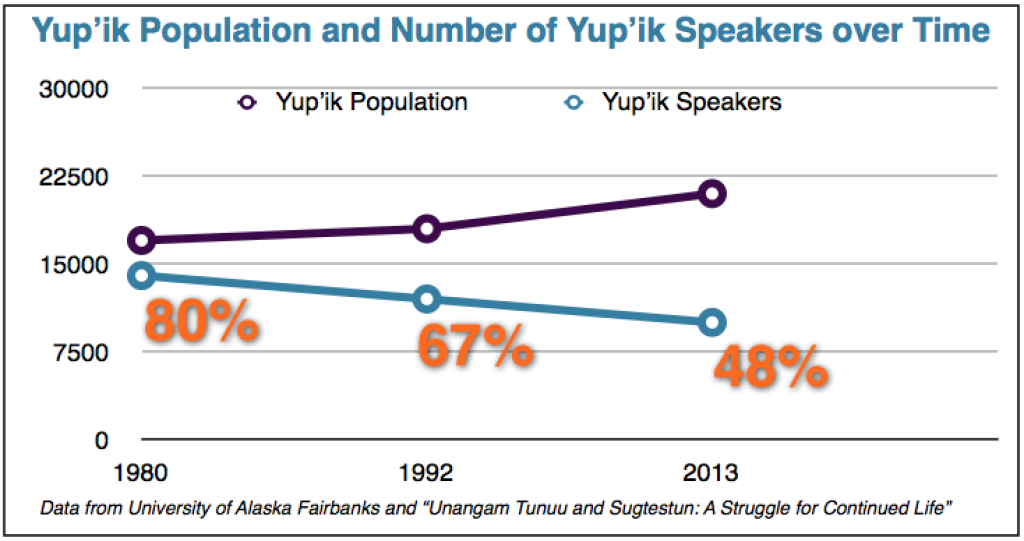

Yup’ik is the most common language in the state of Alaska, apart from English, and the second most spoken Native language in the United States. While these numbers seem impressive, other statistics reflect that Yup’ik language and culture are threatened. Of the 21,000 Yup’ik people in the state of Alaska, only 48% speak the language. Yup’ik is spoken by children as a first language at home in merely 17 of the 68 Yup’ik villages in Alaska. Since 1980, a trend has become clear: Yup’ik population is increasing, and the number of Yup’ik speakers is decreasing. In the past 35 years, the percent of Yup’ik speakers has fallen from 80% to 48%.

Many efforts are being made by individuals, organizations, and communities in order to maintain the Yup’ik culture. Some of these efforts include bilingual education programs, a culturally grounded math curriculum, and digitization of traditional knowledge. Social media has also served as a platform for cultural knowledge and pride for pages and groups such as Alaska Native Languages, I am Yup’ik, and I Sing You Dance.

The online heritage group, Alaska Native Languages, quoted John to have said, “Pass on our language – it’s our strength, our identity.”

Despite the decline suggested in data, the Yup’ik community continues to pursue cultural preservation, empowered by the words of elders such as John.

“Paul John encouraged us to have a foot in each door. Culture and Education, a good way to save our heritage,” said Bethel Resident Caroline Sanders in a Facebook post.

On Saturday, the online cultural pride page, I am Yup’ik, posted, “Paul John, beloved Elder, teacher and Native advocate passed away today. His contribution to preserving the Yup’ik ways of life and words of wisdom will be carried on for generations to come. He will be greatly missed.”