It is an overcast Saturday morning at the National Crafts Museum in Delhi, India. The tinkering of metal work, the rhythm of drums, and the singing of folk songs set the backdrop for a creative atmosphere, where over a dozen artists in residence demonstrate their crafts.

Mohd Shafi Nagoo is one craftsman among them, a paper mache artist by trade. With thin, homemade bushes, he paints hundreds of detailed, intricate designs onto paper mache boxes, pencil holders, coasters, and animal shapes.

“My mind is like a computer,” he explains. “I have thousands of designs stored in my mind. It is up to me which one to paint.”

While many people groups around the world struggle to keep their cultural knowledge and skills alive in the face of globalization, India’s craft industry has continued to adapt and thrive.

In Pursuit of Art

Nagoo is a 55-year-old man with tall, full hair to match his thick mustache. A set of glimmering silver-rimmed glasses match his confidence and intellect. He speaks carefully, with long pauses, and often smiles as he talks.

“Thirty years,” Nagoo ponders as he studies the various paper mache boxes laid out on the floor, a homemade single-hair brush resting in his right hand. “Yah, thirty years I have been in this work.” His hands are steady; his eyes are sharp.

For Nagoo, his artist life began after he completed high school in his home state, Kashmir. At that time, he chose to pursue the master artist, Hazi Mohammad Yousuf Lone, and ask to be taught the traditional craft of paper mache. Nagoo spent years learning from his teacher, creating work, and selling pieces.

“He is a good man. He is my teacher,” Nagoo explains, and then pauses as a smile erupts across his face. “And now, he is also my father-in-law,” he laughs.

Nagoo married Lone’s daughter, Zareena Shafi, who also learned the craft of paper mache from her father. Together, they had two sons, Nadeem and Najmul, who are now in their 20’s and are fully trained on Paper Mache skills, as well. For them, the craft has become a family business and identity, maintaining a line of 7 generations.

Mohd. Shafi Nagoo describes the process of creating traditional paper mache boxes (Video by Victoria Nechodomu/Nechodomu Media).

Crafts of India

Dr. Ruchira Ghose is the chairman of the National Crafts Museum, an organization seeking to educate the public about India’s crafts, while also directly supporting artist. “India is incredibly rich in craft traditions of all kinds, with an enormous variety of products and craft skills across the entire country,” Ghose explains.

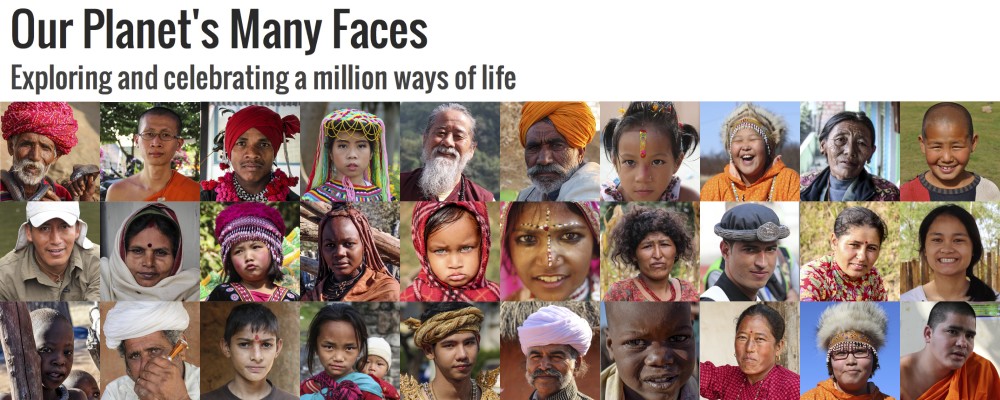

With 29 states spread over an area of about 3 million square kilometers, India is one of the world’s largest countries. As of 2011, the nation’s population was 1.2 billion people representing many distinctive cultures speaking 780 languages. The vast and ancient arts of India range from folk dances to pottery, jewelry making to painting.

“It would be difficult in a few words to describe all the different types of traditional craft by region…India is the country of the handmade,” says Ghose.

The crafts of India are diverse and vary from region to region. Click on the regions above to learn more about the traditional crafts in that area. (Infographic by Victoria Nechodomu/Nechodomu Media)

Globalization and Changing Times

Globalization is defined as, “the growing interaction of societies, economies, and cultures around the world.” The topic has generated much discussion regarding the preservation of culture, language, knowledge, skills, and craft.

India’s craft market has flourished under the impacts of globalization, seeing a 20% increase per year in what Ghose describes as, “much more than passing fad.” Yet the craft market has still faced its share of challenges.

“The value of this handicraft is in Europe side, not here,“ he explains. According to Nagoo, the largest market for crafts in India are European tourists, and that targeting that market is the only way to make a living from the trade.

“It’s really difficult,” he describes. “In India, they are poor. They don’t have money. They would buy this, but they haven’t money. This is problem.”

With the increase of an international market, many artists have struggled to find their place in this changing world and the evolving craft market. According to Handmade in India: Traditional Craft Skills in A Changing World:

“The majority of India’s artisans suffer from severe limitations in accessing and understanding viable new markets, as well as in adapting their products to those markets. In addition, they must deal with the fact that the markets themselves are in a state of transition.”

Perseverance of Indian Crafts

“You cannot make this with machine,” Nagoo declares animatedly, when asked if he thinks factories and technology have had an affect his line of work. He points out intricate details on some of the boxes closest to him, details that could not be replicated by machine. For this reason, Nagoo is confident in the outlook for handmade crafts in India.

Ghose also believes that the demand for handmade items is what will preserve the traditional knowledge and skills of Indian crafts.

“Certainly there is a trend away from the mass produced and towards more individual and unique products, which the handmade caters to,” explains Ghose. “The reason for the resurgence of crafts is complex – driven by need for cultural identity, assertion of aesthetic individuality, economics, sustainability, and is fuelled by technology.”

For Nagoo and his family, who have adapted well to a globalization and a changing market, traditional craft has paid off. With a wife, two grown, educated sons, a nice house, three prestigious national awards for his work, and international artist residencies, Nagoo considers his life and career a success.

“Crafts represent so much of what we are – a multitude of narratives, our myths and legends, our rituals, our aesthetics, are embedded in them,” explains Ghose. “Particular crafts may languish and die but craft in general will survive.”