A wooden boat, heavy with luggage, food, and equipment for a week spent deep in the jungle, creeks as it drifts slowly and quietly past a sandy bank in Manu National Park, Peru.

“See the broken plant by the river, and the tracks in the sand?” Ryse Humani, owner of Bonanza Tours, says, as he motions towards the bank. He explains to his passengers, a small group of international travelers, how the clues add up to a human presence on the beach, and a fairly recent one at that. This particular spot of the river is one where Humani and other guides with Bonanza Tours have encountered what he refers to as “wild” natives, one of the many tribes of uncontacted natives in the Amazon Jungle.

“They wear no clothes, and their skin looks hard from the sun and the mosquitos,” Humani describes. “Usually they go back into the jungle if they hear the boat.” Humani has been aware of this tribe for several years, and he and the other guides have learned to keep a respectable distance from the tribe, if they are sited.

The Manu River is one of over 1,000 tributaries of the Amazon, and falls within a region reported to have at least 70 remaining uncontacted tribes, according to Survival International, an advocacy group for indigenous people groups.

The term, “Uncontacted” is debatable among various organizations and anthropologists. Some, such as Anthropology professor Greg Downey, suggest that the term implies unrealistic expectations that these groups of people have truly never had contact with the outside world. In his article, The Last Free People on the Planet, he writes, “I was personally ambivalent about the use of the word, ‘uncontacted,’ as well as pointed out how clear the Portuguese sources such as FUNAI were that the groups were not‘previously unknown’ or ‘newly discovered.’ ”

Regardless of terminology used, one item most experts seem to agree upon is the intention and message received from these tribes: that it is by choice that these tribes remain ‘off the grid.’ Survivor International attributes this to traumatic events in the past. Their article, Why do they Hide, states, “Many tribal people who are today ‘uncontacted’ are in fact the survivors (or survivors’ descendants) of past atrocities. These acts – massacres, disease epidemics, terrifying violence – are seared into their collective memory, and contact with the outside world is now to be avoided at all costs.”

A Reason to Emerge: A Threat Stronger than Guns

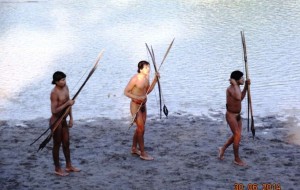

The buzz of uncontacted tribes has been reignited recently by rare footage that was released by FUNAI, Brazil’s National Indian Foundation. The footage, which quickly went viral and was covered by various news outlets, shows two young indigenous men from an uncontacted tribe, wearing nothing but a strap around their waists, and some black markings on their faces, making their way across the river to accept a bundle of bananas from an interpreter.

According to accounts given by both FUNAI and Survivor International, the tribe was escaping violence from outsiders, with reported deaths and burned down buildings. This is consistent with concerns expressed over movements of isolated Amazon tribes due to illegal logging throughout the jungle.

Additionally, it was confirmed that members of the tribe were treated for acute respiratory infections before returning to their homes. This fact has opened up a concern for a threat that is even greater than guns. Historically, great numbers of indigenous people have been destroyed by foreign diseases brought in by outsiders upon contact.

What does the future hold for these groups?

Humani believes that it is inevitable that the uncontacted tribes of Manu National Park will “become civilized soon,” and that it is a good thing for the tribes. “They look sad, living in the jungle.”

For organizations such as Survival International, however, the question is not weather or not contact is good for such tribes. Rather, it is a concern of who initiates that contact, as they have a right to their privacy and culture. And perhaps, underlying it all is an even greater question.

Downey writes in The Last Free People on the Planet, “these are the last free people on this planet. Can we take ‘no, please go away,’ for an answer or must we drill under their forest to stave off, for a few more years, the recognition that we must eventually learn to live within our means? In a way, the last isolated tribes ask us if we’ve learned anything from the sacrifice of all the other isolated tribes before them. Is our planet big enough for more than one world, or must we have it all?”

Stay informed and learn more:

FUNAI: The Brazilian National Indian Foundation, a protection agency for the country’s indigenous people

Survival International: An advocacy group for indigenous groups around the world. This website contains articles, photos, statistics, and footage from various indigenous populations.

Uncontacted Tribes: An advocacy group focussed on evidence of the existence of such tribes.

Turning a Blind Eye: an article by Anthropolgy Professor, Greg Downey, providing possible insights, explanations, and motives for the first-contact scenarios that became a media buzz in 2008.

The Last Free People on the Planet: another article posted by Greg Downey, following up on many points in his 2008 article, and diving deeply into many of the social, political, and ecological contributors to the discussion of “Uncontacted Tribes.”

More Sightings, Violence Around Uncontacted Tribes: The discussion of caution needed in contact with these tribes, and the violence that has occurred due to misunderstandings in the past.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People: An interesting, though dense, read about the resolutions of the UN regarding the rights of Indigenous People.